WHAT IS RELIGION?

The Wind in the Willows, by Kenneth Grahame, is a book about a group of small, vocal animals who lived once upon a time on the banks of the stripling Thames in Oxfordshire. There is one rather famous chapter in the book called “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn,” and the way the chapter begins is roughly this. A family of otters discovers that a small, fat, otter child named Portly is missing. Rat, who is a water rat, and Mole, who is a mole, decide to go search for him in Rat’s boat, and off they go one morning just before daybreak.

Strange things begin to happen. Rat suddenly hears a scrap of music such as he has never heard before, and then before he knows it, it’s gone. “So beautiful and strange and new,” Rat sings (and since these are British animals you have to imagine the British accent). Rat also has a rather flowery way of expressing himself. “Since it was to end so soon, I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it forever.”

At first his friend Mole can’t hear anything — “only the wind playing in the weeds and rushes,” he says — but then when it comes again, he does hear it; and then, as Grahame writes, “breathless and transfixed, he stopped rowing as the liquid run of that glad piping broke on him like a wave, caught him up, and possessed him utterly. He saw the tears on Rat’s cheeks, and bowed his head and understood.”

Religion is listening the way Rat and Mole listened — which is listening with more than just your ears, of course, which is listening with your heart, with your intuition, with whatever is that part of you that longs, like a castaway, to hear news from across the seas. Worship is a response to that news, hearing it even in the ancient words of our forbears who themselves were listeners, who heard and then spoke of what they heard — Shema ’Yisrael, adonai Elohenu, adonai echad. Ecce agnus Dei qui tollit peccatum mundi.

Maybe it’s misleading to speak of religion as listening to something, maybe listening through would be more accurate — listening through the silence, through the prayer, through the music, through the sound of the wind in the rushes or through the sound of your own life, for whatever is to be heard beneath these things. It is listening the way a child listens or the way an animal listens for all I know, without any presuppositions about what you are going to hear or what you are not going to hear.

When you hear something like what Rat and Mole heard, what do you call it? Rat called it music that struck him dumb with joy and at the same time sent tears running down his cheeks. As for me, I would call it the sense that not the world certainly, not existence, but whatever it is that existence itself comes from, the power or ground out of which our lives spring, wishes us well, you and me, wishes to restore us to itself and to each other. It is the power that ultimately all theology and worship is about. It is the power that stirs inside us at those rare moments when we make the effort of real speech with each other, and with it.

— Phil Ellsworth, Rector

St Stephen’s Church, Belvedere, CA

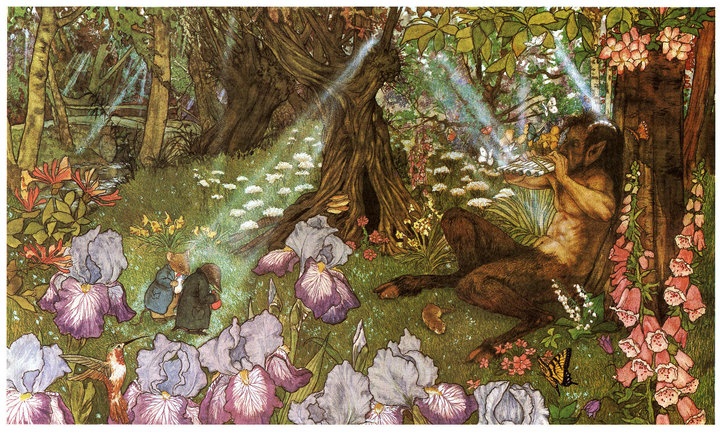

One of the books I read again and again is Kenneth Grahame’s *The Wind in the Willows*. In this scene, Rat and Mole find at last the fat little otter child Portly sleeping peacefully at the feet of the great Pan himself. Here’s how the scene I refer to above continues.

For a space they hung there, brushed by the purple loosestrife that fringed the bank; then the clear imperious summons that marched hand-in-hand with the intoxicating melody imposed its will on Mole, and mechanically he bent to his oars again. And the light grew steadily stronger, but no birds sang as they were wont to do at the approach of dawn; and but for the heavenly music all was marvellously still.

On either side of them, as they glided onwards, the rich meadow-grass seemed that morning of a freshness and a greenness unsurpassable. Never had they noticed the roses so vivid, the willow-herb so riotous, the meadow-sweet so odorous and pervading. Then the murmur of the approaching weir began to hold the air, and they felt a consciousness that they were nearing the end, whatever it might be, that surely awaited their expedition.

A wide half-circle of foam and glinting lights and shining shoulders of green water, the great weir closed the backwater from bank to bank, troubled all the quiet surface with twirling eddies and floating foam-streaks, and deadened all other sounds with its solemn and soothing rumble. In midmost of the stream, embraced in the weir's shimmering arm-spread, a small island lay anchored, fringed close with willow and silver birch and alder. Reserved, shy, but full of significance, it hid whatever it might hold behind a veil, keeping it till the hour should come, and, with the hour, those who were called and chosen.

Slowly, but with no doubt or hesitation whatever, and in something of a solemn expectancy, the two animals passed through the broken, tumultuous water and moored their boat at the flowery margin of the island. In silence they landed, and pushed through the blossom and scented herbage and undergrowth that led up to the level ground, till they stood on a little lawn of a marvellous green, set round with Nature's own orchard-trees—crab-apple, wild cherry, and sloe.

“This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,” whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. “Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!”

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror—indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy—but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty he turned to look for his friend, and saw him at his side, cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible color, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

“Rat!” he found breath to whisper, shaking. “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid! Of him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!”

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.